Alphamin Resources CEO Boris Kamstra discusses 'Tin Mining' at the Bisie mine in DMC since 2011

Mauritius-based mining company Alphamin Resources bought and began developing at the Bisie tin project in 2011. The company is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, and its DRC project holding company has the Democratic Republic of Congo’s government as a 5% shareholder with the Industrial Development Corporation as an 11% shareholder (expected soon to be 15%). Alphamin is developing a mine and processing plant to mine the most developed of its resource targets, Mpama North, and Boris Kamstra, Alphamin CEO, explains its current status:

“We completed a feasibility study last month; we are now aiming to raise the capital required to build the mine and then start building it,” he states. “We want to be in production by 2018, so my job is to get the money to do that, make sure the team on the ground is doing what it needs to do, and ensure they have what they require to succeed.”

Kamstra considers Bisie more than just a mining project: “It’s in the jungles of the Walikale region, which is a region that has had a difficult recent history from which it is now emerging. The mines location is very remote, but the potential for Alphamin to materially change the region is enormous. Throughout our management team is a very strong component of wanting to be part of a project that makes a difference which ensures that they will make this a success due to the positive impact it’ll have, and how we reduce the challenges in front of us.

“Building and operating a mine at Bisie will not be a simple operation, one has to think through all of the potential issues one may have to confront and develop plans to deal with them. There are no other projects in the world I can think of that have the combination of extraordinarily positive project fundamentals, and a whole development impact attached to it along with many challenges and opportunities. It’s actually a draw for employees and community members sensing economic development; a lot of people have approached us wanting to be part of this.”

Within the latest arm of Alphamin’s tin mining project operating between 2017 and 2018, a processing plant will be built to produce around 9,000 tonnes of tin in concentrate per year. The company has had to adopt a unique approach to its supply chain due to the remote location: “It’s a little tricky in that many of the roads we are going to be using are not passable by your average truck,” says Kamstra. “So what we are planning to use is a shunt system.

“We’ll have six-by-six or eight-by-eight military-type vehicles that can carry a 20-tonne container, and this will run between a suitably located depot and the mine. We are going to have to consolidate all our supplies and logistics at one depot, and that will be everything from diesel right through to consumables. These will then be packed into specially designed containers for the trip to the mine. Once unloaded they will return with twenty tons of tin concentrate packed into them.”

According to Kamstra, logistics and transport are less important than they would be for less valuable materials which require efficient bulk transport systems. “We manage logistics in a pretty basic and fundamental way,” he says. “We’re using a combination of existing technologies and readily available solutions in the area, and we incorporate the relevant ones that work for us into our operational plan.”

Far from wishing to corner the DRC market for itself, Kamstra hopes that Alphamin will prove to be a catalyst for other companies to come to the area: “If other businesses come in, that’s to our advantage and to that of the North Kivu province. The more companies you have operating, the more business will emerge. This has multiple effects in terms of economic activity; it’s like a snowball. It continues to roll and makes everything easier for everyone.

“We are in the tin market because we believe the price pressure for tin is going to come from the supply side rather than the demand side. The reason for that is historic; tin was largely a forgotten commodity until its incorporation into solder, and it’s rather tricky to find economically viable deposits of tin. Prices have flown up recently; they did die down a little reaching a low point at the beginning of the year, but we’re delighted to see they have started to improve recently.

“It is estimated that the industry needs tin prices of about $22,000 a tonne in order to provide sufficient feed from 2018 onwards, because other projects that are waiting in the wings require that kind of price to get going. However, we’re doing okay at the current pricing. It gives us a robustness and ability to absorb market gyrations which makes for a very nice business model while we move into production before 2019.”

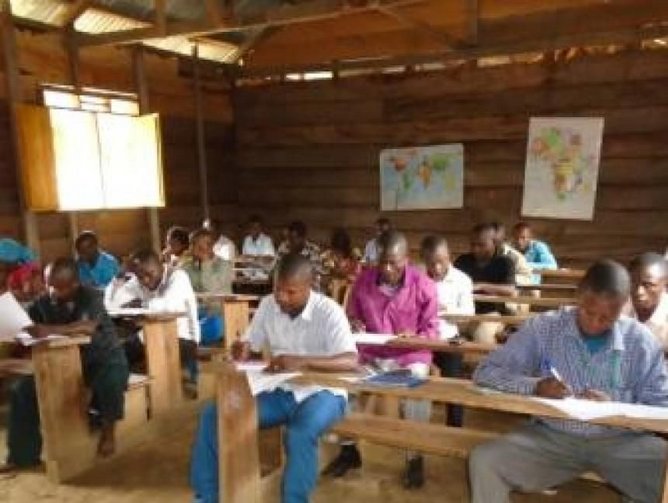

The DRC, Kamstra explains, is an incredibly wealthy area from a natural resource perspective. “Mining, hydrocarbons, agriculture, forestry, fresh water for cultivation and hydroelectricity – it has everything in abundance. However, when the US conflict mineral legislation came out in 2010, the informal tin mining industry in the DRC collapsed because they could not get decent prices, as the material was not certified as conflict-free. Despite this potential wealth, very little benefits of minerals extraction have reached local populations historically in the DRC and especially from recent illegal artisanal production of conflict minerals. Therefore Alphamin has committed to a relatively strong community social investment of 4% of operating expenditures to be invested in local economic, health, education and social infrastructure through a community-driven not-for-profit.

“Alphamin can offer absolutely clean, 100% certified conflict-free tin from this region, so our end users will be assured of a continued supply of tin, which is something a lot of people are getting worried about and that it will be easily verifiable as conflict free. We are developing a secure supply of fundamental material for the modern economy, our customers will have to expend almost zero money ensuring it’s conflict-free, and by purchasing the product, they are materially improving the lives and general wellbeing of the local people. That’s a high-value proposition for the tin industry in general and certainly for most end users.”