The great Palabora copper mine could well be history by now. At the time of the global financial crisis in 2008 the implementation of an expansion plan to extend the mine’s life for a further 20 years was in doubt. The high copper volumes obtained from the original open cast mine, which created the ‘biggest hole in South Africa’ having been largely exhausted, and the 'Lift I' underground mine, whose production capacity reached 30,000 tonnes of ore per day, was nearing the end of its life. A number of years later Palabora's other main product, iron ore in the form of magnetite, was also in decline as world mineral prices plummeted. The simple fact that today Nick Fouché is in his position as General Manager for Growth and Major Projects Delivery at Palabora Mining Company (PMC) shows that this situation has changed radically!

In 2011 Fouché was working in Salt Lake City with the Capital Projects Group of the mine's then principal shareholder Rio Tinto when he was asked to lead an 'order of magnitude' study at Palabora as part of a process to determine whether the massive investment that would be needed to open up a deep mine below the one we have mentioned, would be feasible. “Because we had good drill results and good modelling from previous years we were able to run that study in a nine months as opposed to the couple of years it would normally take,” he says.” time was of the essence, because the new mine, Lift II, needed to take up production and human capacity seamlessly as Lift I declined. Palabora is Southern Africa's only producer of copper rod and many local industries like cable manufacturers depend on it for their supply. A hard stop on one followed by a hard start on the new mine would have made no economic sense.

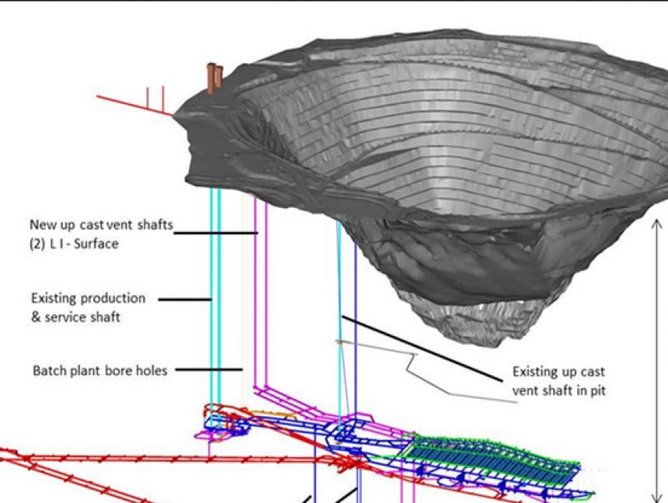

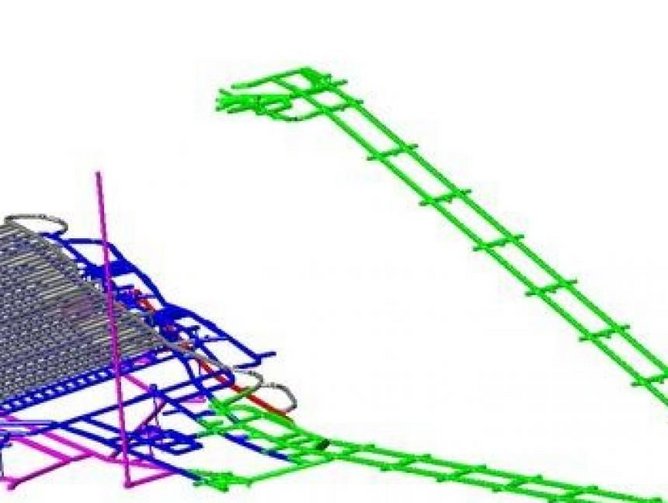

Rio Tinto decided following a feasibility study that the proposed mine would be viable and backed the initial investment to construct the declines that would connect the Lift I and Lift II ore bodies. “We started those ramps in early 2012,” Fouché explains. “At that stage we realised we would have to optimise the design. If the upfront capital requirement was too high the grade of our reserve would not support it. We had to leverage the existing shaft infrastructure, and build a second bock cave under the existing one, connect them all up and still make a positive business case out of it!” They decided on a twin-decline ramp system to connect the ore bodies. One decline is for people and supplies, the other is a conveyor decline each 3.6 kilometres in length.

Pushing the boundaries

The key requirement was to get the tunnels advanced quickly. “We started rather late, so we called for a 10.5 metre daily advance on two faces, though most contractors wouldn't commit to more than seven.” The challenge was taken up by the Australian contractor Byrnecut, which managed to achieve this unprecedented advance rate, at the same time as training a local workforce in the skills needed for high speed mechanised development. An innovative contract was devised to spread the risk between owner and contractor in recognition of the uncertainties of the project and the fact that the advance rate was at the threshold of previous mining practice. It still couldn't have been done without the deployment of a massive 21 tonne LHD. “We lowered the machine using our existing shaft infrastructure, and that is the biggest piece of mobile equipment that has been lowered in a shaft in Africa,” recalls Nick Fouché “We had to do some clever engineering. We built a special skeleton for the machine so that we could stay within the loading limits of our winder. This kind of initiative really energised the project: we are doing things here that are pushing the boundaries of conventional mining!”

An additional uncertainty was injected in 2013 when Rio Tinto withdrew from Palabora and PMC was acquired by a consortium led by the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) of South Africa Limited and China’s Hebei Iron & Steel Group. The investment case had to be sold to the new shareholders. The fact that much of the infrastructure was in place impressed the new shareholders and they supported the Lift II project despite the fact that their primary interest had been the magnetite, of which there was a 250 million tonne stockpile at the mine.

In November 2014 the board approved the Lift II investment programme of more than a billion dollars says Fouché : “We took the view that though prices were depressed we had enough financial carry to cover a lot of the upfront work from our own balance sheet, and went to the market for some of the funding.” At the same time, with the copper price on the floor contraction set in among other copper projects as some were shelved, mothballed or abandoned. “We have taken a positive view of the long term copper price. The supply and demand position projected post 2020 indicates that copper prices would potentially be on the rise.” To develop an underground copper mine takes many years, he adds. Four years from now PMC may face competitive supply in an improving world minerals environment.

Cutting the cloth

But copper prices are still low and Palabora needs to guard its margins. One way it is doing this is by taking out cost and using local contractors where possible. Byrnecut was successful but cost was dollar based and potential existed for a lower cost approach, so in March it was decided to change to a small South African company Mvuso which would have a lower cost base, the goal was to share our knowledge and help them to reach a competitive mining rate. “We have a lot of in-house expertise: we have been tunnelling with Byrnecut for more than three years, and we have been running a block cave for 15 years after all. Reconfiguring and repricing the tunnelling work has taken out hundreds of million’s of Rand, he says, and the move has been justified since the local contractor has added 2.5 kilometres to the tunnels and has reached the access point to the undercut, from which the ore will flow.

The focus now is on ventilation. To connect the Lift I and Lift II ventilation systems PMC has sunk two 450-metre shafts, 4.5 metres in diameter. The contractor, Murray & Roberts will then connect the undercut and production levels with a number of raisebores. That's going smoothly, however the twin ventilation shafts being sunk from the surface present a real challenge. The contractor Master Drilling is once again approaching the limits of mining capability: the company designed and built the RD8 raiseboring machine specifically for the PMC project, which entails the construction of two 6.1-m-diameter ventilation shafts, each with a record-breaking depth of 1.2 Kilometres. The RD8 machine operates faster and is significantly cheaper than the conventional blind-sinking technologies, and requires only two operators per shift. But raiseboring has never been tried at this depth and diameter in combination. “The driver for us is that we were looking to maximise the vent requirement without doing multiple holes: the bigger you go the lower the cost is a theme running throughout the project. We need to stay in the cost envelope and engineer accordingly.”

The traditional approach to project management is that the owner's team oversees the EPCM and the EPCM oversees the contractors. On Lift II it made sense to leverage the expertise of the people who had been involved in Lift I construction – after all they are very similar in design. Accordingly, Fouché and his team have worked out a more integrated management approach with the EPCM contractor RSV (Reid Swatman & Voigt). “It saves us a lot of money and the teams I manage are so much more positive since there are no shadow roles. Decision making is quicker, team dynamics are better – we do things together and there's no 'them and us' blame culture!”

Special cases

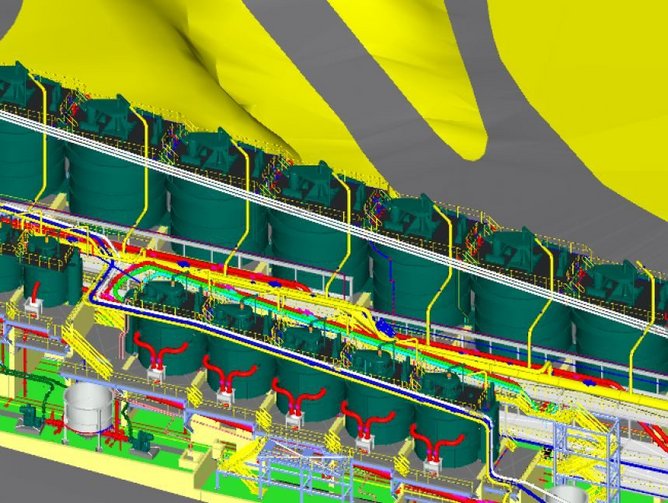

The 40 year old process plant at Palabora has become more costly and inefficient, so it's being replaced. “We are building a brand new flotation plant with just 14 major float cells (the current plant has around 78 float cells), so you already get huge economies of scale on energy, pumps, maintenance and other things. The new plant will be volumtrically more substantial, which means more recovery time and improved recoveries. We will push recoveries up from around 83 percent to 88 or 89 percent,” explains Fouché. The plant is under construction by Beijing General Research Institute for Mining and Metallurgy (BGRIMM), which is fast becoming a major player in Africa. Another major project he is overseeing is an ore sorter to remove granite content which can linger in the autogenous mills, taking up space that should be filled with ore and reducing throughput

But by far the largest upgrade will be the smelter which produces copper rod for the domestic market. It was built to cater for the original open cast operation which produced 80,000 tonnes per annum (tpa) of pure copper from a throughput of up to 120,000 tonnes per day (tpd) of ore. The present day operation produces about 41,000 tpa from 3,000 tpd. “The size of the furnace does not match our production footprint, and that means huge inefficiencies through heat loss and a very costly downstream process,” he says. The smelter is being retrofitted at a total cost of $55 million, the entire furnace is being replaced and new technology introduced throughout, it will be effectively a new smelter. At the time of writing the project was still under tender.

As mentioned earlier PMC is not a pure play copper producer. The magnetite circuit, upgraded last year with the purchase of a new separation plant and a drying plant that can handle 6 million tpa adding a price premium of five to eight dollars a tonne to the product, is of immense importance to the company. This revenue goes a long way to fund the Lift II project, says Fouché “Now that everyone is struggling with iron ore, it is the ones with the low grade that are falling out of the market. We are in a good position to continue to produce iron ore to supply foreign markets.”

A future for Phalaborwa

With so many major projects to oversee it is a miracle that Nick Fouché has time for anything else, but he retains his passion for PMC's sustainability agenda. Thanks to Lift II the mine will still be here till 2033, maybe a little longer, but it will run out one day and PMC's responsibility will not end there. “I set a vision for the project: when we leave we must leave something substantial behind more than just a mine. I want to see new contractor companies that are sustainable going forward and can be part of the mining economy.” We want the project to contribute to the transformation agenda of the country and the region, encouraging and supporting previously disadvantaged groups to be long term sustainable suppliers to our industry. In addition to this we want the existing Palabora Foundation which has been a flagship in the mining industry, he adds to be able to continue its good work in its support to our community and the sustainability of our business. It supports many initiatives in our community from small scale farming to harvesting amarula, a tree found only here and from which liqueur and cosmetics are made.

It also runs after-school programmes for AIDS orphaned children, clinics and job creation schemes as well as supporting supplier development start-ups. We have started a process where many small construction companies in the district, whose expertise was limited to small dwellings and community buildings, have been invited on to the mine and given small surface projects and then in collaboration with larger contractors they are brought underground to construct sub-stations and the like. “As a result of this process we have spent large sums of money on contracts for black-owned and women-owned enterprises,” says Fouché. My hope is that these contractors will reach a point where they are tendering across multiple mines and industries not only in Palabhorwa but across the country.

Another form of contribution towards sustainability has been to contractually define the hiring policy of semi skilled and unskilled labour. For the last two years it has been a condition of any contract at the Lift II project that all unskilled and 80 percent semi-skilled labour is sourced from the Ba-Phalaborwa district's of 150,000 population. It's a policy with real impact in a region with upward of 50 percent unemployment. I think that is one project that has found real traction,” he concludes. “I am proud of what we have done with the magnetite upgrade, the Lift II construction, the downstream plant and the communities. Palabora is a flagship in southern Africa.”