In 2016, there are still just a handful of services which are deemed crucial to a thriving community — though running water, housing and electricity are invariably among them. However, with the advent of the Internet, our idea of what constitutes an ‘essential’ utility has had to expand.

Deloitte research has shown that productivity in developing countries could be enhanced by as much as 25 percent with the expansion of WiFi access. For countries like South Africa, where 75 percent of citizens can’t easily or affordably get online, it is not yet possible to compete with industrialised, knowledge-based economies. Project Isizwe, a not-for-profit organisation based in the city of Tshwane, is currently working with government bodies across South Africa to bring free public WiFi to the country.

“We all understand the value of Internet connectivity,” Zahir Khan, the CEO of Project Isizwe, explains, “especially in terms of educational benefits, improved healthcare services, better opportunities for economic development — and, of course, social cohesion. From that perspective it’s critical to connect the country sooner rather than later.”

In 2013, a bid to connect every citizen was launched across the city of Tshwane. To date, it is Project Isizwe’s largest deployment effort, with 850 Free Internet Zones (FIZs) installed in the local area and almost two million unique users accessing the web since November of 2013. By 2018, Tshwane will have WiFi within walking distance of every citizen.

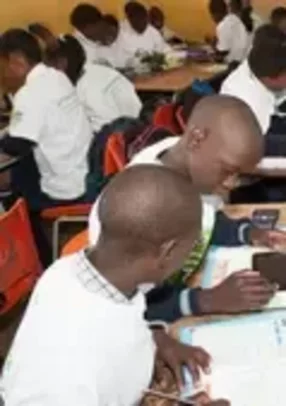

Project sponsors hand-select the hotspot locations based on their perceived value for the surrounding community. It is this kind of thinking which led to the installation of 213 Internet access points outside of schools in Tshwane.

“The city has funded the provision of public access WiFi on their infrastructure outside of these schools,” Khan says. “This ensures that every learner, educator and community member in and around the schools is connected”.

Rural environments in South Africa also stand to benefit from the efforts of Project Isizwe, though installation in these locations is admittedly more of a challenge. The large majority of financial backing for WiFi installation comes from a locality’s government and public sector bodies. In more remote regions, state revenue is limited, thus it is more difficult to get these communities online. Ultimately, Project Isizwe hopes to have an Internet access point within five kilometres of every rural citizen.

“Funding has been the biggest barrier for expansion across the entire country,” Khan says. “In five different provinces — Limpopo Province, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape, Western Cape, and Gauteng — the biggest barrier to expansion of the free Wi-Fi offering is the availability of funding.”

Project Isizwe’s not-for-profit status has enabled it to reduce the cost of installing telecoms infrastructure by what Khan describes as a “significant” margin. With the help of its partners, the project operates exclusively under cost-recovery: it doesn’t charge users for its service and the large-scale financial benefits of WiFi access for South Africa will not be immediately evident.

“We are essentially three times more affordable than traditional deployments of network companies,” Khan says. “We have been fortunate enough to have great OEM and Infrastructure partners that assist us in these reductions of price as they too firmly believe that bridging the digital divide will ultimately form a stronger and more active economy for South Africa.”

Research by the World Bank has shown that a 10 percent increase in what is called ‘broadband penetration’, the amount of the Internet access market that has been captured by high-speed broadband, will result in a 1.3 percent increase in a country’s GDP.

“The [financial] sustainability of Government funded public space free WiFi comes out of the long-term benefit of enabling Internet access for citizens today,” Khan says.

Historically, access to an affordable mobile device — be it a smartphone, tablet or laptop — was also a barrier to Internet access in South Africa. Khan notes that, in recent years, as the cost of these items has fallen, they have made their way into the hands of people all over the country.

Project Isizwe has deployed in rural environments, places as remote as the mountain village of Tshedza in Limpopo province,” he explains, “even there you’ve got people with WiFi-enabled devices who can utilise and connect to the network. Devices are not the issue any longer.”

As impediments to Internet access and availability are dissolved across South Africa, people are finding creative ways to reach out into their newly-connected world. Khan cites the story of Martin Nyokolodi, a young man in Tshwane who has launched his own Internet radio station, among his favourites. Not only does Nyokolodi utilise the City’s ‘TshWi-Fi’ service to broadcast his programme, he also takes Skype calls from listeners and maintains the station’s social media presence on the network.

The benefits of connectivity have also been extended to the healthcare and hospitality sectors. Restaurant owners in proximity to a WiFi hotspot have been setting up shelters within signal range so that customers can access the web. Khan reports that these makeshift ‘Internet cafes’ have increased restaurant profits by as much as 80 percent. Equally, the Internet has helped to streamline the process of care and diagnosis in South Africa’s clinics and medical facilities.

In its National Development Plan 2030, the government of South Africa states that it wants universally available Internet across the country in 14 years’ time.

“There’s a lot for us to do,” Khan admits.

However, Project Isizwe, and its CEO, realise the transformative impacts that Internet access can have over lives and economies — and they will go forward knowing just how tremendous the return on public space free WiFi investment will be.

“The public hotspots become a place to bridge the digital divide, where regardless of personal circumstance or background, everyone has access to the same Internet,” Khan says.